network+ guide to networks

Network+ Guide to Networks: An Overview

This comprehensive guide delves into networking fundamentals, covering models, layers, devices, media, addressing, and security – essential for aspiring IT professionals and certification seekers.

Networking, at its core, is about connecting devices to share resources and information. This foundational element of modern IT involves understanding how data travels between computers, servers, and other networked components. The journey begins with grasping basic terminology – nodes, links, protocols, and topologies – forming the building blocks of any network.

Different network types exist, ranging from small home networks (LANs) to vast global networks like the internet (WANs). Understanding these distinctions is crucial. Furthermore, the concept of layered models, like the OSI and TCP/IP models, provides a structured approach to comprehending the complex interactions within a network. These models break down networking functions into manageable layers, each with specific responsibilities.

This introduction will lay the groundwork for exploring these concepts in detail, preparing you to navigate the intricacies of network communication and design. It’s a vital first step towards mastering network administration and troubleshooting.

The Importance of Networking in Modern IT

In today’s digital landscape, networking is no longer a supporting function – it is the foundation of modern IT. Businesses, governments, and individuals rely on networks for nearly every aspect of their operations, from communication and data sharing to critical infrastructure and cloud services. Without robust and secure networks, productivity grinds to a halt, and innovation stagnates;

The increasing reliance on cloud computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), and remote work has further amplified the importance of networking skills. Professionals with a strong understanding of networking principles are in high demand, tasked with designing, implementing, and maintaining these complex systems.

Moreover, network security is paramount. Protecting sensitive data from cyber threats requires a deep understanding of network vulnerabilities and security protocols. Mastering networking is therefore essential not only for enabling connectivity but also for ensuring the safety and reliability of the digital world.

Networking Fundamentals

Core concepts encompass network models, protocols, and data transmission methods, forming the bedrock of communication. Understanding these principles is vital for effective network management.

OSI Model: A Layered Approach

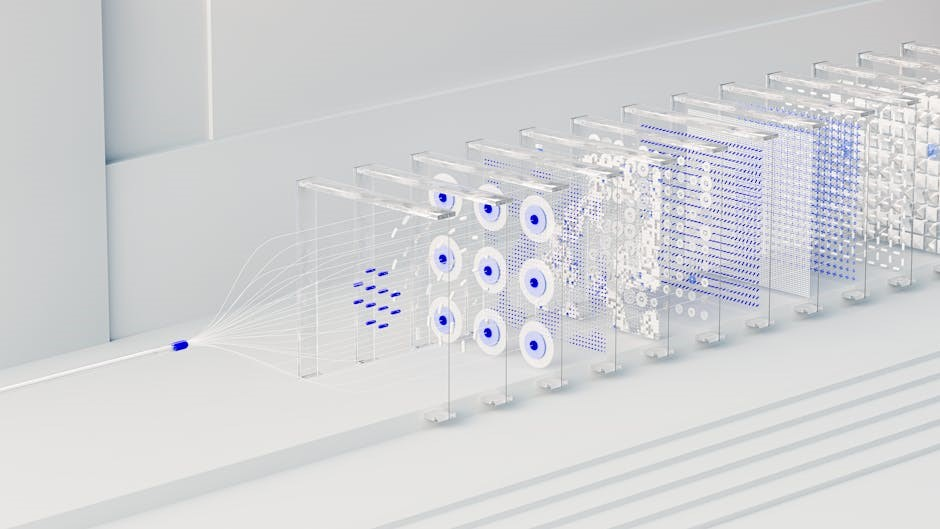

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model is a conceptual framework that standardizes the functions of a telecommunication or computing system into seven abstract layers. It provides a modular approach to network communication, allowing for interoperability between different systems and technologies. Each layer performs a specific set of functions, building upon the services provided by the layer below it.

This layered structure simplifies troubleshooting and development, as issues can be isolated to a specific layer. The seven layers, from top to bottom, are: Application, Presentation, Session, Transport, Network, Data Link, and Physical. Understanding each layer’s role is crucial for comprehending how data travels across a network. The model isn’t a physical implementation, but a reference point for understanding network interactions and protocols. It’s a foundational element in networking education and certification, like the Network+.

Layer 1: The Physical Layer

The Physical Layer is the foundation of the OSI model, dealing with the actual physical connection between devices. It’s responsible for transmitting raw bit streams over a communication medium. This layer defines characteristics like voltage levels, cabling standards, and physical connectors – essentially, how bits are physically represented as signals.

Key aspects include data rates, transmission modes (simplex, half-duplex, full-duplex), and physical topologies (bus, star, ring). Common technologies at this layer encompass copper cabling (like Cat5e, Cat6), fiber optic cables, and wireless signals. The Physical Layer doesn’t interpret the meaning of the data; it simply conveys it. Troubleshooting at this layer often involves checking cables, connectors, and signal strength. Understanding this layer is vital for diagnosing connectivity issues and selecting appropriate media for network infrastructure.

Layer 2: The Data Link Layer ⸺ MAC Addressing & Ethernet

The Data Link Layer provides error-free transmission of data frames between two directly connected nodes. It’s primarily concerned with physical addressing using Media Access Control (MAC) addresses – unique identifiers assigned to Network Interface Cards (NICs). Ethernet is the dominant technology at this layer, defining how devices access the network medium.

This layer divides data into frames, adds header information (source & destination MAC addresses), and performs error detection. It utilizes protocols like ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) to map IP addresses to MAC addresses. Switching occurs at Layer 2, forwarding frames based on MAC address tables. Collision detection and avoidance mechanisms are also crucial functions. Understanding MAC addresses and Ethernet standards is fundamental for network troubleshooting and configuring network devices. Proper Layer 2 operation ensures reliable communication within a local network segment.

Layer 3: The Network Layer ⸺ IP Addressing & Routing

The Network Layer is responsible for logical addressing and routing data packets between different networks. Internet Protocol (IP) addressing, both IPv4 and IPv6, is central to this layer, providing a hierarchical system for identifying devices globally. This layer determines the best path for data to travel from source to destination, a process known as routing.

Routers operate at Layer 3, examining destination IP addresses and forwarding packets accordingly. Routing tables, populated statically or dynamically through routing protocols, guide these decisions. Key concepts include subnetting, which divides networks for efficiency, and the use of routing metrics to determine optimal paths. The Network Layer ensures packets reach their intended destination, even across multiple networks, forming the backbone of internet communication. Understanding IP addressing and routing is vital for network design and troubleshooting.

Layer 4: The Transport Layer ⸺ TCP & UDP

The Transport Layer establishes end-to-end communication between applications. Two primary protocols operate here: Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP). TCP provides a connection-oriented, reliable service, ensuring data arrives in order and without errors through mechanisms like acknowledgements and retransmissions. It’s ideal for applications requiring data integrity, such as web browsing and email.

UDP, conversely, is connectionless and offers a faster, but less reliable, service. It doesn’t guarantee delivery or order, making it suitable for applications where speed is paramount, like streaming video or online gaming. Port numbers are crucial at this layer, identifying specific applications or services running on a host. The Transport Layer segments data from the Application Layer and reassembles it at the receiving end, managing flow control and error checking to ensure efficient communication.

TCP/IP Model: The Practical Implementation

The TCP/IP model is the foundational architecture of the internet, a practical application of networking concepts. Unlike the theoretical OSI model, TCP/IP comprises four layers: Application, Transport, Internet, and Network Access. The Application layer encompasses protocols like HTTP, FTP, and SMTP, enabling software applications to communicate. The Transport layer, utilizing TCP and UDP, manages reliable or unreliable data delivery between hosts.

The Internet layer, centered around the IP protocol, handles logical addressing and routing of data packets. Finally, the Network Access layer deals with the physical transmission of data, incorporating technologies like Ethernet and Wi-Fi. This model’s simplicity and robustness have made it the dominant standard for network communication, providing a framework for interoperability and scalability across diverse networks globally. Understanding TCP/IP is crucial for any networking professional.

Network Hardware & Devices

Essential components like routers, switches, hubs, and NICs facilitate network communication; each device plays a unique role in directing, connecting, and enabling data transmission.

Routers: Directing Network Traffic

Routers are pivotal in network architecture, functioning as traffic directors between networks. They analyze destination IP addresses within data packets and intelligently forward them along the optimal path towards their intended recipient. Unlike switches operating within a single network, routers connect multiple networks – think of your home network connecting to the internet.

Key router functions include path selection using routing tables, Network Address Translation (NAT) which allows multiple devices to share a single public IP address, and often, basic firewall capabilities. Modern routers support various routing protocols like RIP, OSPF, and EIGRP to dynamically learn and adapt to network changes. They come in various forms, from small home routers to large enterprise-grade devices handling massive data flows.

Understanding routing is crucial for Network+ certification, encompassing concepts like static vs. dynamic routing, default gateways, and the impact of routing metrics on network performance. Properly configured routers ensure efficient and secure data delivery across interconnected networks.

Switches: Connecting Devices Within a Network

Switches are fundamental components for connecting devices within a local area network (LAN). Unlike hubs which broadcast data to all connected ports, switches intelligently learn the MAC addresses of connected devices and forward data only to the intended recipient, significantly improving network efficiency.

Operating at Layer 2 (the Data Link Layer) of the OSI model, switches utilize MAC address tables to make forwarding decisions. They support various features like VLANs (Virtual LANs) for network segmentation, Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) to prevent loops, and Quality of Service (QoS) to prioritize traffic. Managed switches offer advanced configuration options, while unmanaged switches are plug-and-play.

For Network+ certification, understanding switch operation, port security, and troubleshooting common issues is vital. Switches are the backbone of most modern networks, providing reliable and high-speed connectivity for devices within a localized environment, enhancing overall network performance.

Hubs: Basic Connectivity (and their limitations)

Hubs represent the most basic form of network connectivity, functioning as a central connection point for devices in a LAN. However, they operate at the Physical Layer (Layer 1) of the OSI model and lack the intelligence of switches. When a hub receives data, it broadcasts it to all connected ports, regardless of the intended destination.

This broadcasting nature creates significant limitations, including increased network collisions and reduced bandwidth efficiency. As all devices share the same collision domain, only one device can transmit at a time, leading to performance bottlenecks, especially in busy networks. Hubs also offer no security features like VLANs or port security.

While largely obsolete in modern networks, understanding hubs is crucial for the Network+ exam. Recognizing their limitations highlights the advantages of switches and other more advanced networking devices. They serve as a historical stepping stone in understanding network evolution and basic connectivity principles.

Network Interface Cards (NICs): The Gateway to the Network

Network Interface Cards (NICs) are fundamental hardware components enabling devices to connect to a network. Often referred to as network adapters, they provide the physical interface between a computer and the network medium – whether it’s Ethernet cable or a wireless signal. NICs operate at both the Physical and Data Link Layers (Layers 1 & 2) of the OSI model.

Each NIC possesses a unique Media Access Control (MAC) address, a hardware address used for identification within the local network. NICs handle tasks like framing data, error detection, and managing data flow. Modern NICs support various speeds (e.g., 10/100/1000 Mbps) and features like auto-negotiation to optimize connection speed.

Understanding NICs is vital for troubleshooting network connectivity issues. They are essential for all networked devices, from computers and servers to printers and IoT devices, acting as the crucial bridge for communication. Proper NIC configuration and driver updates are key to reliable network performance.

Network Media

Network media encompasses the physical pathways for data transmission, including copper cabling, fiber optics, and wireless signals, each offering unique characteristics and performance capabilities.

Copper Cabling: Twisted Pair (Cat5e, Cat6, Cat6a)

Twisted pair cabling remains a prevalent choice for Ethernet networks due to its cost-effectiveness and ease of installation. The “twisted” pairs of wires help reduce electromagnetic interference (EMI) and crosstalk. Several categories exist, each offering improved performance.

Category 5e (Cat5e) supports Gigabit Ethernet over 100 meters, making it suitable for many home and office networks. Category 6 (Cat6) provides even better performance, reducing crosstalk and supporting 10 Gigabit Ethernet over shorter distances. It’s a good upgrade for demanding applications.

Category 6a (Cat6a) further enhances performance, offering full 10 Gigabit Ethernet capabilities over the standard 100-meter distance. It features tighter twisting and shielding, minimizing interference. Choosing the right category depends on bandwidth requirements, distance, and budget. Proper termination and testing are crucial for optimal performance, utilizing tools like cable testers to verify connectivity and signal quality.

Fiber Optic Cabling: Speed and Distance

Fiber optic cabling utilizes light signals to transmit data, offering significant advantages over copper, including higher bandwidth and longer distances. It’s immune to electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI), ensuring reliable data transmission.

Two primary types exist: single-mode and multi-mode fiber. Single-mode fiber has a smaller core, allowing a single light path, ideal for long distances (kilometers) and high bandwidth applications like internet backbones. Multi-mode fiber has a larger core, enabling multiple light paths, suitable for shorter distances (hundreds of meters) within buildings.

Fiber offers superior security as it’s difficult to tap without detection. Connectors like LC and SC are commonly used. While more expensive than copper and requiring specialized equipment for termination and testing (using optical power meters), the performance benefits often justify the cost, especially for demanding network environments. Careful handling is essential to avoid damage to the delicate fiber strands.

Wireless Networking: Wi-Fi Standards (802.11 a/b/g/n/ac/ax)

Wireless networking, based on the 802.11 standards, has revolutionized connectivity. Early standards like 802.11b and 802.11a offered limited speeds. 802.11g improved upon ‘b’ with faster rates, while ‘a’ operated on a different frequency. 802.11n introduced Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) technology, significantly boosting speed and range.

802.11ac (Wi-Fi 5) further enhanced performance with wider channels and more spatial streams. Currently, 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6) is the latest standard, focusing on efficiency in dense environments, utilizing technologies like Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access (OFDMA). Each standard operates on different frequencies (2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz) with varying ranges and interference susceptibility.

Understanding these standards is crucial for network design and troubleshooting. Factors like channel selection, security protocols (WPA2/WPA3), and proper antenna placement impact wireless performance. Newer standards offer improved security and efficiency, making them ideal for modern network demands.

Network Addressing

Network addressing schemes, like IPv4 and IPv6, are fundamental for device identification and communication. Subnetting optimizes network efficiency, while DNS translates names into addresses.

IP Addressing: IPv4 and IPv6

IP (Internet Protocol) addressing is the cornerstone of network communication, providing a logical address for each device. IPv4, the fourth version, utilizes 32-bit addresses, represented in dotted decimal notation (e.g., 192.168.1.1). However, the exhaustion of IPv4 address space prompted the development of IPv6.

IPv6 employs 128-bit addresses, offering a vastly larger address pool and resolving the limitations of IPv4. Its hexadecimal notation (e.g., 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334) allows for a significantly increased number of unique addresses. IPv6 also incorporates features like autoconfiguration and improved security.

Understanding the differences between these protocols, including address formats, subnetting capabilities, and header structures, is crucial for network administration and troubleshooting. Transition mechanisms, such as dual-stack and tunneling, facilitate the coexistence of IPv4 and IPv6 networks during the ongoing migration process. Proper IP addressing is vital for efficient and reliable network operation.

Subnetting: Dividing Networks for Efficiency

Subnetting is a crucial technique for dividing a larger network into smaller, more manageable subnetworks. This enhances network performance, security, and organization; By borrowing bits from the host portion of an IP address, you create distinct network segments.

The process involves calculating subnet masks, which define the network and host portions of an IP address. Understanding binary conversion and bitwise operations is essential for accurate subnetting. Subnetting reduces broadcast traffic, improves network security by isolating segments, and optimizes IP address allocation.

Proper subnetting allows for efficient use of IP address space and simplifies network administration. Concepts like Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) further refine address allocation. Determining the appropriate subnet mask depends on the number of hosts required in each subnet. Mastering subnetting is a fundamental skill for any network professional, enabling effective network design and troubleshooting.

DNS: Translating Names to Addresses

The Domain Name System (DNS) is the internet’s phonebook, translating human-readable domain names (like google.com) into machine-readable IP addresses (like 172.217.160.142). This process is essential for accessing online resources without memorizing complex numerical addresses.

DNS operates as a hierarchical and distributed database. When you type a URL, your computer queries a DNS resolver, which then contacts a series of DNS servers to find the corresponding IP address. These servers include root servers, Top-Level Domain (TLD) servers, and authoritative name servers.

Understanding DNS records – such as A, MX, CNAME, and NS records – is crucial for network administration. DNS caching improves performance by storing frequently accessed translations. Security considerations include DNSSEC, which adds authentication to DNS data, preventing spoofing and other attacks. A functional DNS is vital for seamless internet connectivity.

Network Security Fundamentals

Protecting networks involves firewalls, threat detection, and vulnerability management. Understanding common attacks—malware, phishing, and denial-of-service—is key to building robust defenses.

Firewalls: Protecting the Network Perimeter

Firewalls are crucial for network security, acting as a barrier between a trusted internal network and untrusted external networks, like the internet. They meticulously examine incoming and outgoing network traffic based on pre-defined security rules. These rules dictate which traffic is permitted or blocked, effectively controlling network access.

Different firewall types exist, including packet-filtering firewalls, which analyze data packets, and stateful inspection firewalls, which track the state of network connections. Next-generation firewalls (NGFWs) offer advanced features like intrusion prevention systems (IPS) and application control, providing deeper inspection and protection.

Proper firewall configuration is paramount. Incorrectly configured firewalls can create vulnerabilities or disrupt legitimate network traffic. Regular rule reviews and updates are essential to adapt to evolving threats. Firewalls are a foundational element in a comprehensive network security strategy, safeguarding valuable data and resources.

Common Network Threats and Vulnerabilities

Networks face a constant barrage of threats, demanding robust security measures. Malware, encompassing viruses, worms, and Trojans, aims to disrupt operations, steal data, or gain unauthorized access. Phishing attacks deceive users into revealing sensitive information, often through fraudulent emails or websites.

Denial-of-Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks overwhelm network resources, rendering them unavailable to legitimate users. Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks intercept communication, allowing attackers to eavesdrop or manipulate data. Ransomware encrypts data, demanding payment for its release.

Vulnerabilities often stem from weak passwords, unpatched software, and misconfigured network devices. Social engineering exploits human psychology to gain access. Regularly updating software, implementing strong passwords, and educating users about security best practices are vital for mitigating these risks. Proactive threat detection and incident response planning are also crucial components of a strong security posture.